Surrey Suicide Prevention Strategy 2023 - 2026

The Surrey Suicide Prevention Partnership is a multi-agency collaboration between health, local government, people with lived experience and the voluntary and community (VCS) sector. This strategy refresh sets out our approach to reducing suicide in Surrey based on national and local intelligence/ evidence, local learning and national suicide prevention recommendations.

Introduction

In Surrey approximately 92 people a year die by suicide, each death by suicide is a devastating loss of life and behind these statistics are families, friends and communities bereaved by suicide. With each and every suicide, there are shockwaves sent through families and communities.

Around 14 people die by suicide every day in England (ONS, 2021).

From 2001 to 2018, suicide and injury or poisoning of undetermined intent was the leading cause of death for both males and females aged 20 to 34 years in the UK (ONS, Leading causes of death, UK: 2001 to 2018, 2020)

Globally suicide is also the fourth leading cause of death among 15-19 year-olds (WHO, 2021).

Each suicide has far reaching consequences, affecting a number of people directly and many others indirectly with those affected often impacted economically, psychologically and spiritually (McDonnell S, November 2020). Family, friends and carers of those who die by suicide have a 1 in 10 risk of making a suicide attempt after experiencing loss. Thus, suicides lead to the worsening and perpetuating cycle of inequalities (Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, 2016).

It is estimated that nationally, around one third of those who die by suicide in England have been in contact with mental health services in the 12 months leading up to their death, and a further third have seen their GP but are not receiving specialist mental health support (Department of Health, 2017). Self-harm (including attempted suicide) is the single biggest indicator of suicide risk and approximately 50 per cent of people who have died by suicide have a history of self-harm (Department of Health, 2017).

Suicide is often the end point of a complex history of risk factors and distressing events. The prevention of suicide has to address this complexity. As there is no single risk factor for suicide, the prevention of suicide does not sit with any single organisation. In many cases, suicide can be reduced through identification of risk, public health interventions and high quality evidence-based care.

A robust multi-agency suicide prevention approach needs to take place at individual and population levels and so needs the input of people with lived experience of mental health, people bereaved by suicide, front line services, commissioners and policy makers.

The Surrey Suicide Prevention Partnership is a multi-agency collaboration between health, local government, people with lived experience and the voluntary and community (VCS) sector. This strategy refresh sets out our approach to reducing suicide in Surrey based on national and local intelligence/ evidence, local learning and national suicide prevention recommendations.

Policy context

Suicide prevention remains at the forefront of health priorities in many countries, including England. The national Suicide Prevention Strategy in England, consisting of a cross-government outcomes strategy to save lives, was first published in 2012 . Its key aims are to reduce the suicide rate in the general population in England and better support those bereaved or affected by suicide. It was updated in 2017 to including tackling self-harm as an issue in its own right.

To support the strategy, the NHS asked that all CCGs should deliver local multi-agency suicide prevention plans. The strategy included a commitment to reduce the rate of suicides in England by 10% by 2020/21 (compared to 2015 levels). The most recent progress report, published January 2019, showed that there was a 9.2% reduction in suicides.

The appointment of the UK's first Prevention in 2018 marked the government's renewed commitment to forward evidence-based practices for suicide prevention and outreach across the UK.

The NHS Long Term Plan committed to spend £2.3 billion annually on mental health services by 2023/24 and to widen the coverage of NHS England's and NHS Improvement's suicide prevention programme. This national programme has allowed NHS and local Integrated Care Board and Integrated Care Partnership to be set up and enable dedicated suicide prevention work to take place locally including implementing a new Mental Health Safety Improvement Programme and rolling out suicide bereavement support services across the country.

Mission statement for Surrey

We aspire that no one in Surrey should die by suicide.

As a county we seek to reduce suicide. To achieve this ambition will require a collective commitment by the key partners to develop an action plan to deliver the 'What we will do' sections set out in each key priority area.

Reducing suicides in Surrey

1. Lived experience

Co-production will be at the heart of the suicide prevention work. The voice of people with lived experience of suicide and people bereaved by suicide will be embedded across the Surrey suicide prevention work. A trauma informed care approach will be used to ensure that Surrey develops frameworks to ensure that people with histories of trauma are supported throughout the system.

2. Whole Family Approach

Interventions, prevention and system response will be considered across the whole family. There will also be a clear read across with key strategies such as the Helping Families Early Support Strategy and the Perinatal Strategy. Families will be included in care plans for both children and adults. The voice and experience of the family will be embedded across suicide prevention.

3. Life Course Approach

A life course approach will be applied through the Suicide Prevention Programme in Surrey, specifically for preparation and response to key life events and transition points.

4. Culture

In Surrey we aim to reduce the stigma around suicide by raising awareness on mental health stigma and suicide stigma:

- We aim for a culture where people use language that encourages people to talk about suicide openly and without judgement.

- We aim for a culture where people are supported to access support in a timely manner.

- We aim for a culture where learnings from the frontline can be shared and used to inform system developments for timely, responsive support.

- We aim to develop channels to ensure voices of those working in and receiving services are heard and use of education and awareness to change the attitudes of the community, frontline services, commissioners and senior leadership to ensure that there are no barriers to accessing support.

To ensure that a trauma informed approach is embedded across Surrey we will embed a culture where:

- Individuals and their families/ loved ones are empowered to contact services for support and services provide an atmosphere that enables people to feel supported and acknowledged.

- Individuals and their families/ loved ones are given choices and control over care, support and treatment that they receive.

- Decisions on care, support and treatment are made openly and transparently with individuals and their families/ loved ones.

5. Evidence base

The Suicide Prevention Programme will be informed by evidence including national guidance and research, Surrey Suicide Audit (2017-2021), real-time suicide surveillance, local learning and local engagement.

6. System ownership

The Surrey system will collectively own suicide prevention and take responsibility for the delivery of recommendations and identified actions within this Suicide Prevention Strategy.

As part of a system-wide approach the partnership will develop a Surrey Suicide Prevention Protocol. Every partner that is part of the partnership group or commissioned to deliver services as part of the strategy will be required to sign up to a Surrey Suicide Prevention Protocol. This will enable shared awareness, knowledge and ownership of the agenda and not just 'buy -in.' The protocol will be supported by appropriate training and toolkits to ensure all partners have the ability to implement changes. The protocol will be considered in the governance reporting to ensure sustained application and to provide support where needed.

To ensure that suicide prevention is embedded across the system it is recommended that strategies and partnership groups which have cross-representation of suicide prevention partners also ensure that suicide prevention is included in their plans and where possible they also consider signing up to the Surrey Suicide Prevention Protocol.

7. Governance

The Suicide Prevention Strategy Oversight Group will report to the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Board. On a regular basis the group will also report to key partnerships. This will include the children's safeguarding, adult safeguarding, mental health delivery board and the clinical quality and safety boards.

The governance of the suicide prevention partnership will be through the below structure. This will enable clear delivery and accountability of key priority areas and actions. This approach will enable two way leadership; top down ownership by leaders of partner organisations and strategic planning and bottom up from the frontline to raise barriers and challenges to implement changes.

Alignment with the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy

The suicide prevention strategy supports Priority 2 of the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy.

The key outcomes for this priority are:

- Adults, children and young people at risk of and with depression, anxiety and other mental health issues access the right early help and resources

- The emotional well-being of parents and caregivers babies and children is supported

- Isolation is prevented and those that are feeling isolated are supported

- Environment and communities in which people live work and learn build good mental health

Structure of Surrey suicide prevention partnership and governance arrangements

Oversight group - meet every 8 weeks

- An overall suicide prevention oversight group with 5 - 10 members. This group will report into the Surrey Suicide Prevention Strategy group.

As part of the oversight group an extraordinary meeting for networking group: meet quarterly - input / show and tell.

| Group 1 Prevention and early intervention | Group 2 Mental health services and commissioning | Group 3 Learning and postvention |

|---|---|---|

| Education and awareness | Commissioning | Postvention support |

| Building resilience | Service provision | Suicide response |

| Early intervention | Service delivery | Learning from serious incidents related to attempted suicide or self-harm |

| Families support | Service needs, gaps | Postvention support |

| Service development | ||

| Recovery |

All partners that are part of the suicide prevention partnership will be required to sign up to the Surrey suicide prevention protocol. This will ensure that each partner has suicide prevention embedded in their wider policies and across their organisation and supported by their senior leader.

Key progress 2019 - 2022

Suicide prevention partnership in Surrey was developed in 2007. In the 2019-2022, for the first time there was an allocated budget to enable the development and delivery of key actions identified in the strategy. Previous to this there was ad hoc funding.

As a result of this funding a lot of progress was made towards the actions and recommendations in the 2019-2022 strategy. Through this we have been able to identify further opportunities for suicide prevention and learning from suicide. These have been embedded in this strategy.

The below figure shows key progress from 2019-2022.

Workforce development

- Over 70 suicide prevention training courses have been delivered

- 200 people have completed SafeTALK training

- 500 people have completed Suicide First Aid training

- Pre COVID suicide prevention training course was co-designed and delivered to GPs via SABP

- Zero Suicide Alliance training has been promoted across Surrey

- During the first year of Covid 1,000 staff attended mental health first aid aware.

Emerge Advocacy - support in A&E for children and young people

Emerge Advocacy provide short term support for young people who find themselves in A&E because they are struggling with self-harm or feeling suicidal.

In 2021 they were commissioned to offer a service in all the A&Es in Surrey.

Safe Haven

There are now five adult Safe Havens and four children and young people Safe Havens in Surrey.

Surrey real-time suicide surveillance

In 2020 a post was recruited in Surrey Police to set up and manage the Surrey real time suicide surveillance database.

Suicide response work

As a result of the Surrey real time suicide surveillance database, a multi-agency system has been developed to carry out a systematic response to suspected suicides.

Suicide bereavement

A suicide bereavement service in Surrey was developed by a family bereaved by suicide.

A referral process is in place starting from the real time surveillance. To date the service has supported over 300 people bereaved by suicide.

Suicide in Surrey

There is no single determining cause of suicide. Instead, suicide is often a response to a combination of factors that can include wider determinants of health, mental health and physical health.

Between 2017 and 2021 there were 258 deaths by suicide in Surrey. In 2021 Surrey Public Health Team commissioned an audit of deaths by suicide. Coroners' files were reviewed to understand the key contributing risks to suicide, access to services and opportunities for suicide prevention. However, there are a number of caveats. These are early findings, and the pandemic is still current. It is also too soon to examine the effect of any economic downturn. Serious economic stresses as a consequence of Covid-19 coupled with the cost of living crisis since 2022 may represent the greatest risk of a rise of suicide. These overall national figures may mask increases in suicide in population groups or geographical areas, as we know the impact of the acute pandemic has not been uniform across communities. Mental health charities have highlighted an increase in use of their helplines throughout the pandemic .

Deaths by suicide in Surrey Key Facts from suicide audit

The key facts shown are based on an audit of Coroners' files which identified 258 deaths by suicide in Surrey between 2017 and 2020.

- 65 is the average number of deaths by suicide per year of Surrey residents

- Approximately three quarters of those who took their own life were male (76%) and a quarter were female (24%)

- The most common age group was 45 - 59 years. One third of deaths by suicide were in this age group

- The majority of individuals (71%) who died by suicide were categorised as 'white', 7% were categorised as other (Asian, Black, African, Caribbean and other Asian) and 5% categorised as European.

Please note as this data is from Coroners' records it differs from the data on PHE fingertips.

The mean age at death was 53 for males and 41 for females (48.2 overall), with the highest number of deaths, one third, in the 45-59 years age bracket.

The most common method of death was hanging accounting for 54% of suicides in the audit.

65% of deaths occurred in the deceased's own home, with 35% in a more public place or workplace.

36% of people who died lived alone, and 36% were not in a long term relationship of any sort. Approximately a quarter (27%) of Surrey residents live alone according to the 2011 census.

Individuals who died by suicide had many complex needs. One in five were recorded to have a disability, one in three had a history of violence and abuse (either as perpetrators, victims or both), and one in three had a previous history of self-harm.

- By far the most common mental health condition that individuals had who died by suicide was depression. Over half had either a clinical diagnosis of depression or had documented in their clinical notes that periods of depression had occurred over their lifetime. One third had an anxiety condition.

- 57% acknowledged either alcohol or substance use before death. This largely covers individuals who had a combination of long established alcohol use and/ or drug misuse. However, only 3% of the individuals who died by suicide were in contact with specialist substance misuse service prior to death, 1% in the previous 3 months, 3% in the last 12 months and 3% over 24 months.

- Just over half of individuals who died by suicide shared their suicidal thoughts with someone. The majority did so with a family member, closely followed by a health professional.

- The strongest risk factor for suicide is a previous suicide attempt, and 37% of individuals who died by suicide had a previous suicide attempt.

- 51% of the individuals for whom information about mental health was available were in contact with mental health services.

- A quarter of individuals who died by suicide were in contact with a mental health service at the time of their death.

- Over the 4 year period this has been quite consistent with an average of 51% of individuals who died by suicide having contact with mental health services and 45% having with no contact with mental health services.

- 4% visited their GP in the preceding 24 hours to death and 1 in 5 individuals had a GP visit up to 2 weeks before death. The highest proportion of individuals, equating to just over a quarter (28%), visited over 3 months prior to death. The reasons for the visit varied between a mental health issue, a physical issue, both issues or just a routine appointment. There was no obvious pattern.

- At post-mortem, drugs and/ or high levels of alcohol were found in the system of the deceased in 57% of cases, suggesting that half of all cases were under the influence of drugs/ alcohol at the moment they took their own life.

- There is also a close link between drug related deaths and suicides. There have been some cases of drug related death that could have been suicide; and some suspected suicides that were later deemed as drug related deaths.

COVID-19 pandemic: impact on mental health

Emerging evidence confirms that 1.5 million children and young people in England will need support for their mental health as a direct result of the pandemic over the next three to five years.

An early study into COVID-19 and mental health in the UK found that 69% of adults in the UK report feeling somewhat or very worried about the effects of COVID-19 on their lives. The most common issues affecting wellbeing are worry about the future (63%), feeling stressed or anxious (56%) and feeling bored (49%) (Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, 2020)

Key findings from the Surrey COVID-19 Community Impact Assessment (CIA) and Mental Health Rapid Needs Assessment (RNA) (Surrey PH , 2020) included:

Pre-pandemic the mental health services (provided by the NHS and as well as VCS) were facing a number of challenges before the pandemic, including:

- Lack of funding and resources

- Insufficient workforce for service delivery

- High thresholds for meeting the criteria in order to receive psychological support, although some stakeholders felt that this was due to inappropriate consideration of the level/ type of intervention and insufficient usage of lower level mental health interventions

- Fragmented care pathways (in particular dementia services)

- Access barriers due to physical barriers (location, timing, availability of appointments)

- Insufficient outreach to certain groups such as BAME, homeless, drug and alcohol dependent individuals.

- Some VCS organisations also highlighted a lack of awareness about their organisations' support offer by GPs and other partners across Surrey who may come in contact with people with mental health needs.

Groups have not been equally impacted by COVID-19. Young adults and women – groups with worse mental health pre-pandemic – have been hit hardest. There was also greater impact on people with pre-existing long-term conditions and those are clinically vulnerable (shielding) as well as those with drug and alcohol dependencies.

Evidence also suggests that the economic shock of COVID-19 has had an almost immediate effect on people's mental health. Both the Mental Health Foundation and ONS have reported far higher levels of anxiety among those financially impacted by the pandemic. One fifth of people surveyed by the Mental Health Foundation, who identified as unemployed, reported suicidal thoughts in the previous fortnight.

Key recommendations

Communication

- Effective communication to raise awareness about mental health services and how/ when they can be accessed by the public and by the professionals for signposting.

Building capacity and investment

- Build capacity and invest in VCS and charity organisations to enhance community-based support

- Investment in prevention of mental ill health and empower the people to self-care

- Investment in 24/7 community helpline and crisis lines, alternatives to admission and strengthening community services to help people to stay well and avoid escalations

- Investment in adult social care mental health services to ensure the increasing numbers of people with more complex needs are supported to stay well in their communities, which will enable whole system efficiencies.

Improve access and support

- Improving access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services particularly for older, people with long-term conditions and those from BAME groups

- Develop a support offer particularly for people with dementia living on their own

- No "wrong door" policy for people with dual diagnosis and reducing barrier in referring people with a drug and/ or alcohol issue to Community Mental Health Recovery Services (CMHRS)

- Extension of the Integrated Mental Health Support in Primary Care (GPIMHS) in GP practices offering support in Primary Care

- Improve mental health care pathways by enhancing service integration to prevent people from falling through the gaps

- Increase in mental health training offer to frontline staff, volunteers and community call handlers

- Putting in place local offers to support health and social care frontline staff, ensure they have access to PPE and testing.

Addressing mental health inequalities

- Investment to reduce digital inequalities

- Addressing the determinants of poor mental health that are being affected by COVID-19, such as financial difficulties and debt, unemployment, bereavement, domestic violence and abuse, risky alcohol consumption, substance misuse, and gambling addiction

- Inequalities in mental health to be put "front and centre" of all planning and service recovery and development. This should be through increasing investment in Voluntary Community Sector and peer support programmes to improve access to services

- Implement a robust suicide prevention action plan at District and Borough level in line with Surrey Suicide Prevention Strategy.

Partnership working

- Embedding the partnership working in future sustainability, collaboration and innovation

- Joined up discussions across commissioning to provide high-quality and sustainable services to improve health and wellbeing.

Learning from suspected suicides

In Surrey, the real time suicide surveillance has given key learnings for the prevention suicides. These have included:

- Identifying key risk locations

- Identifying key methods and opportunities to mitigate risk

- Access to methods and reviewing access

- Key groups at risk and delivering targeted messages and support to these groups.

National Suicide Prevention Strategy

Suicide prevention is everyone's business. Creating a "suicide safer community" will enable a joined up strategic approach to suicide prevention. This will ensure that prevention, intervention, postvention intervention, postvention support and learning are addressed and embedded.

This also enables communities and organisations to take ownership and embed change.

In order to become a suicide safer community it is important to meet ten key areas that have been identified in key national and international suicide prevention strategies:

- Leadership

- Community Needs Assessment

- Mental health promotion

- Suicide Prevention Awareness

- Training community members, laypersons, and professionals in the areas of suicide: prevention, intervention, post-intervention, and postvention.

- Suicide Intervention Services

- Clinical and Support Services Collaborations and Partnerships

- Suicide Bereavement

- Evaluation

- Capacity Building and Sustainability

Surrey will embed all these areas across the Surrey suicide prevention strategy.

Priority areas for Surrey

In Surrey to meet the ten National standards and to address local learnings we will deliver suicide prevention through the six key priority areas.

- Priority 1: understanding suicide and attempted suicide in Surrey

- Priority 2: tailor approaches to improve emotional wellbeing in particular groups

- Priority 3: reduce access to means by promoting suicide safer communities

- Priority 4: reduce attempted suicide amongst children and young people

- Priority 5: provide better information and support to those bereaved by suicide

- Priority 6: prevention of suicide among identified high risk groups particular those with known mental ill health

Priority 1: understanding suicide and attempted suicide in Surrey

Attempted suicide data and self-harm

Due to clinical coding attempted self-harm and suicide data has been difficult to obtain and analyse. It is recognised that a serious self-harm and a real-time attempted suicide learning process is needed in Surrey. The data would provide data to understand the groups at risk, emerging methods and locations of risk. This will inform the prevention work.

Real time suicide surveillance

In 2020 Surrey Police and Surrey Public Health Team set up "Real Time Suicide Surveillance" (RTS). Deaths by suspected suicides where police attend are recorded and reviewed on a daily basis.

The current process for the Surrey real time surveillance process:

- Police attend scene and collect intelligence. Collated data is shared with the real time surveillance lead

- Real time surveillance lead refers bereaved directly to suicide bereavement service

- Real time surveillance data is sent to Public Health

- Public Health Lead reviews data for any epilinks, concerns around location or method, suicide response agreed. Meetings between Public Health Lead, police, clinical leads

- Suicide response work carried out as required.

The current process has enabled Surrey to develop a suicide response process and carry out actions to reduce suicides in Surrey. These have included responding to locations of risk, emerging methods, managing social contagion, and identifying any epi-links between cases.

However, the current process does not allow agencies in addition to Public Health and the Police to add intelligence to the cases, therefore it is not possible to see a personal journey through services or to systematically process intelligence. In addition, the current RTS does not collect deaths by suspected suicide where the person has died in hospital.

Plans are in place to roll out a nationally recognised Suicide Surveillance System in Surrey that will enable other agencies to add intelligence. This will enable Surrey to have a collaborative suicide learning process.

Suspected suicide response

In 2021 a Surrey suicide response process was set up. This identified key criteria for stepping up the response.

The suicide response is set up if the below criteria is met:

- Suicides in groups vulnerable to imitation (e.g., users of education setting, psychiatric setting)

- More suicides than expected within a time frame within a specific location

- More suicides than expected within a time period which are geographically widespread

- Suicides involving particular methods

- Suicides occurring in the same location as previous clusters but after some time.

In a six month period this process was stepped up thirteen times.

The process for the suicide response is:

- Instigate the response group to meet within 24 hours

- Collate information and share with response group

- Identify and map others that maybe vulnerable

- Ensure that postvention support is offered and available

- If method - work with key agencies as appropriate to identify ways to reduce this method

- If location - work with key agencies as appropriate to identify ways to identify how the location was accessed, what mitigation could be put in plan and ensure this is reported to the appropriate leads for that location

- Identify any key risks mentioned in the case files and identify ways to reduce these and ensure this is reported to the appropriate leads to manage

- Review local media

- Develop communications messages as appropriate.

Each suicide response requires on average 30 hours' officer time.

When there is a death by suspected suicide in a young person Public Health attend the Surrey child death information sharing meeting organised by the Child Death Nurse. This information sharing meeting is part of the child death review process. The key role for Public Health is to identity epidemiological links (geographical, social and psychological) with the view to offer bereavement support and review and manage any social contagion.

An action plan is created after each suspected suicide that is predominantly following on the gaps in information and to offer support for those identified as risk. Public Health hold accountability for the plan and key elements are delivered by the appropriate leads.

18 - 25 year olds

The child death review process only covers up to the day before the eighteenth birthday. In Surrey it has been identified that 18 – 25 year olds need to have a death review process. A key reason is that this is an age of transition from sixth form/ college to university, and the transition between education and work.

The Surrey data also shows that in 0 – 24 year olds, over 75% deaths were in young people aged 18 - 25.

Joint suicide learning process

When there is a sudden death by suspected suicide, each organisation has internal reporting and investigation processes that identify opportunities for learning. People who die by suicide and have accessed mental health support usually have been in contact with a number of services through their treatment/ therapy journey. In Surrey there is an opportunity to join up the learning from these processes. A streamlined learning process would enable Surrey to map a person's journey through services and identify opportunities for prevention, intervention and service development.

What the Surrey Suicide Prevention partnership will do

- 1.1 Expand the real-time surveillance work to triangulate the data with key services.

- 1.2 Develop a real time attempted suicide learning process.

- 1.3 Develop and deliver a joint suicide learning process.

- 1.4 Ensure that there is a suspected suicide rapid response process in place for 18- 25 year olds.

- 1.5 Employ a suicide response worker in Surrey.

Priority 2: tailor approaches to improve emotional wellbeing in particular groups

LQBTQI

A report by Stonewall (2018), identified that a large number of LGBTQI people have experienced depression, anxiety, had suicidal thoughts or even attempted to take their own life in the last year. Key findings from the report:

- 52% of LGBTQI people said they have experienced depression.

- 13% of LGBTQI people aged 18-24 said they have attempted to take their own life

- 46% of trans people have thought about taking their own life in the last year, 31% of LGB people who are not trans said the same.

The fear of rejection from family, peers and society among young people who identify as trans, at a time of their developing sense of self (sometimes in an emotionally unsupportive environment), can create a sense of 'otherness.' This can leave trans young people particularly vulnerable to depression and suicidal thoughts (Royal College of Nursing and PHE, 2015)

A Home Office funded study (Gender Identity Research and Education 2018), estimated the number of trans people in the UK to be between 300,000 – 500,000 – where trans was defined as 'a large reservoir of transgender people who experience some degree of gender variance'. Applying this estimate to the Surrey population, would lead to an estimate of at least 7,000 trans people in Surrey. (Surrey County Council, Surrey-i , 2018).

Neurodiversity

A review of Coroners' inquest records and family interviews by Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge, found that:

- 10% of those who died by suicide had evidence of elevated autistic traits, indicating likely undiagnosed autism. This is 11 times higher than the rate of autism in the UK

- 6% of autistic adults have thought about taking their own life, and 35% have attempted suicide.

It is estimated that 1% of people in the UK are autistic. Based on this for Surrey it is estimated that the autistic population is 12,000 people. This is made up of:

- 2,500 children aged 0-16

- 1,000 young people aged 17-25

- 8,500 people aged 25 and over.

People of ethnic minorities

Ethnicity is not recorded on the death certificate, as ethnicity is classified as a self-reported characteristic therefore it is difficult to get an accurate picture of the ethnic groups at increased risk of suicide.

A 2021 ONS report found that while not one of the most common causes of death, suicide in males were higher in White and Mixed ethnic groups than in other groups, and in females the rate for the Mixed ethnic group was higher than other groups (ONS, "Mortality from leading causes of death by ethnic group, England and Wales: 2012 to 2019". Locally and nationally, there is anecdotal evidence that mixed heritage could be a risk factor. There is an opportunity to explore this further.

Locally poor reporting and recording of ethnicity is a major limitation of exploring this in a systematic way.

Refugee and asylum

Little is known about the risk of suicide in refugees and asylum seekers. Nationally mental health, suicidal ideation, self-harm, and attempted suicide is frequently not reported; therefore the data for refugees and asylum seekers is poor. However, the trauma that they have experienced will likely increase the risk of poor mental health.

Frontline staff in Surrey working with refugees and asylum seekers report high levels of poor emotional wellbeing, poor mental health and social isolation in this group.

Criminal justice system

Those who have been or who are involved with the criminal justice system commonly face multiple disadvantages including but not limited to: social exclusion, substance misuse, homelessness and mental and physical health problems.

An international study (Seena Fazel, 2017) reviewed suicide rates in prisons across 24 countries. The report calculated that the annual suicide rate for people in prison (sentenced and remand) in England and Wales is 83 per 100,000 of population. This is significantly higher than the general suicide rates in England and Wales. In September 2020 there were 2,600 people in prisons across Surrey (Surrey-i, 2018).

Male prisoners in England and Wales were 3.7 times more likely to die from suicide than men in the general population.

HM Inspectorate of Prisons reported that 71% of women and 47% of men surveyed by inspectors in prison self-reported having mental health problems. In recent years prison suicides self-harm and violence have increased across the prisons .

Targeted work is needed to prevention suicides in the five prisons in Surrey.

It is recommended that the Surrey Partnership works with the prisons to audit the prison suicide prevention plans and offer support and guidance.

General bereavement

From all the Surrey suicide audits grief and bereavement have been identified as one of the top five contributing risk factors. The loss of a loved one can cause grief, sadness, isolation and increased risk of poor mental health.

The capacity for general bereavement support should be evaluated against the need.

Gambling

Research from Gamble Aware and the Gambling Commission identified:

- One in five people had thought about suicide in the past year, compared with 4% of non-problem gamblers/ non-gamblers.

- 5% of problem gamblers reported they had made a suicide attempt in the past year, compared with 0.6% of those who showed no sign of problem gambling.

It is recommended that there is a plan in Surrey to deliver mental health awareness and support to gamblers in Surrey.

Domestic abuse

Domestic abuse is an incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening, degrading and violent behaviour, including sexual violence, in the majority of cases by a partner or ex-partner, but also by a family member or carer.

Key findings - domestic abuse and suicide: exploring the links with Refuge's client base and work force:

- Almost a quarter (24%) of Refuge's clients has felt suicidal at one time or another

- 18% had made plans to end their life

- 3.1% had made at least one suicide attempt

There was strong evidence for psychological distress or injury across the whole sample:

- 86% scored above cut for clinical concern on the CORE-10 measure of psychological distress

- 83% confirmed feeling despairing and hopeless - a key determinant for suicidality

- 96% of those in the suicidal group reported feeling despairing or hopeless

- 49% of the suicidal group scored within the severe range of psychological distress

- 86% of suicidal group reported feeling depressed

In Surrey it is recommended that:

- Suicide prevention is embedded in the domestic abuse services.

- Domestic abuse awareness is embedded in all mental health services.

Long-term physical conditions

Chronic or long-term conditions are generally defined as any condition or health problem lasting longer than 3 months. Generally, having a chronic condition is associated with poorer mental health, with this becoming even more pronounced in people who are living with more than one condition (multimorbidity or co-morbidity). People with chronic conditions, like diabetes, cardiovascular disease or respiratory disease are also more likely to have co-morbid mental illness, like anxiety or depression.

In Surrey, the most common long-term conditions are diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 13.5% of Surrey residents have a long-term health problem or disability. It is estimated that depression rates are likely to be 2-3 times higher in people with a chronic physical condition, and this rate will increase even further for people living with more than one chronic condition.

A comprehensive study from 2017 looked at over 2000 suicides and compared them with matched controls. They found 17 conditions associated with higher risk of suicide, nine of which remained significant after controlling for mental health problems and substance use. These were back pain, brain injury, cancer, heart failure, COPD, diabetes, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, heart disease, hypertension, migraine, Parkinson's disease, psychogenic pain, renal disorders, sleep disorders and stroke. Three conditions which carried a twofold increase in suicide risk – traumatic brain injury, sleep-related disorders and multimorbidity (presence of two or more chronic conditions) – were higher in those who had died by suicide compared to controls. This means that having multiple physical conditions increased the risk of suicide significantly.

A systematic review found that somatic symptom and related disorders are associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. This was independent of co-occurring mental disorders. Additionally, risk factors for suicide attempts in people with somatic symptoms and related disorders included scores on measures of anger, alexithymia, alcohol use, past hospitalisations, dissociation, and emotional abuse.

A review on the suicide risk associated with chronic pain found that suicide risk is significantly higher in people living with chronic pain, but this risk is attributed to the psychosocial rather than the physical aspect of pain. This is consistent with previous literature which found that not just having a diagnosis of a chronic condition, but rather the functional limitation is associated with increased risk of suicide. - Chronic pain and suicide risk: A comprehensive review - ScienceDirect This review is based on a narrative review and a meta-analysis which found robust evidence confirming the link between chronic pain and suicidal ideation, attempts and completed suicide.

A restful sleep is critical to positive health outcomes. Insomnia refers to difficulty getting to sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, early wakening or non-restful sleep. It involves impaired daytime functioning and symptoms such as poor concentration, fatigue and mood disturbance. Chronic insomnia (insomnia symptoms occurring at least 3 nights per week for over three months) is commonly co-occurring with other physical and mental conditions, including anxiety or depression, COPD, heart failure, neurodegenerative diseases, MSK conditions and chronic pain, as well as substance use. Bidirectional effects often exist between insomnia and co-morbid conditions. Research estimates that around a third of adults in Western countries experience sleep problems, and 6-10% meet the criteria for insomnia disorder. This is more common in females compared to males, and more common in older adults. Around half of all people with insomnia have a co-morbid psychiatric disorder.

People with long-term conditions and co-morbid mental health problems disproportionately live in deprived areas and have access to fewer resources. The interaction between multiple conditions and deprivation makes a significant contribution to generating and maintaining inequalities.

Gypsy Roma Traveller (GRT)

Research shows that the suicide rate for members of the Traveller community is six times higher than the general population .

GRT communities collectively represent a significant ethnic minority group in Surrey. It is estimated that there is around 10-12,000 GRT residents, which would mean that Surrey has the fourth largest GRT population of any local authority.

In Surrey there is a need for targeted suicide prevention work with the GRT community.

Alcohol and substance use

The abuse of alcohol or substances increases the risk of poor mental health. However alcohol and substance misuse increase the risk of poor mental health whilst in addition it is evident that having poor mental health can lead individuals to use alcohol and drugs to alleviate their depression or anxiety. It is a difficult circle to manage effectively.

Alcohol and substance use increases risk taking behaviours and increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

In Surrey, 57% of people who had died by suicide had used either alcohol or substance before their death. This largely covers individuals who had a combination of long established alcohol use and/ or drug misuse. However, only 3% of the individuals who died by suicide were in contact with specialist substance misuse services prior to death,

There is also a close link between drug related deaths and suicides. There have been some cases of drug related death that could have been suicide; and some suspected suicides that were later deemed as drug related deaths. The drug related death work and the suicide prevention work should align to share learning and opportunities for joined up intervention.

Older adults

Nationally suicides are increasing in older adults. Key risk factors such as poor physical health, poor mental health, social isolation, retirement, bereavement and changes in social circumstances have been identified in older adults. Additionally in this group there are added risks around thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness and acquired capability issues. In Surrey work is needed to understand the suicide risk in older adults and to ensure that there is a clear prevention and intervention workstream targeting older adults.

Gender and suicide

Since around 2010, males aged 45 to 64 years have had the highest suicide rate.

In Surrey between 2017 and 2021 a quarter of deaths by suicide were in females and three quarters were in males. The most common age group was 45 – 59 year olds. Key risk factors identified in this group included social isolation, relationship breakdown, bereavement, job loss, financial issues, alcohol use and substance use.

Nationally there has been a reported increase in female suicide. We will continue to monitor and review this in Surrey.

Generation X

People born in the 1960s and 1970s are known as Generation X. Now in their 40s and 50s they are dying in greater numbers by suicide or drug poisoning than any other age group.

Research shows that Generation X show poorer physical health, increased rates of depression and anxiety, and higher levels of unhealthy behaviours, such as alcohol use and smoking, compared to previous generation .

Research is needed on Generation X in Surrey.

Social and community network

Although not a predeterminant of suicide itself, feelings of loneliness and isolation are nonetheless consistently linked to behaviours of suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, and outright suicide attempts.

Through the life course, social and community networks will change during key age related transition periods. Starting from education to employment, to maternity/ paternity, to retirement.

Additionally different life course events or being in a certain age bracket will also bring different services into a person's life. The change in these or in some cases the loss of these can impact on a person's wellbeing.

All these changes will result in a loss of connectedness, increased social isolation, reduced social capital and can cause poor mental health. If emotional and mental resilience tools, preparation and services are built into transition this can reduce the impact of poor mental health.

Carers

An overwhelming proportion of adult carers evidence signs of social isolation, with only 22.4% of adult carers reporting they have as much social contact as they would like. This is significantly lower than the Southeast and national proportions, at 31.4% and 32.5% respectively.

Carers are also likely to experience financial concerns, increased poor mental health and a life change due to the caring responsibility. All these increase the risk of suicide.

General socio economic, cultural and environmental condition

16% of people who died in Surrey by suicide between 2017- 2021 had financial issues recorded in their files.

A report by Samaritans analysed young adults who have experienced thoughts of suicide. The report found that financial stability, and economic turmoil are contributing substantially to how young people aged 18-24 are feeling about their lives. Key risks also include job uncertainty, lack of local of opportunities and a lack of hope for the future.

At the point of this report, there were concerns about the increasing cost of living and the serious impact this will have on mental health.

In Surrey during the 2007 recession the suicide rates increased.

Due to the already high cost of living in Surrey, a nationally increasing cost of living taking place since 2022 will hit Surrey residents harder than other parts of England. Support to access key benefits, debt advice and employment support will reduce this risk.

Occupation groups

Surrey real time suicide surveillance for 2020- 2022 shows that specific occupations and those who are not in employment are at increased risk of suicide. To ensure that suicide prevention is targeted at this group it is important that job centres, benefits advisers, employment agencies and workplaces have a mental health plan. This should include building emotional resilience, mental health awareness training, suicide prevention training, referring and signposting people to support.

At risk occupations include doctors, nurses, veterinary workers, farmers and agricultural workers, low skilled occupations, low skilled male labourers and males working in skilled trades (ONS, 2017). This is usually correlated to increased access to financial means. However there are large national variations with these figures.

Blue light services and clinical staff

Surrey hosts large NHS employers including Acute Hospitals (employing doctors and nurses), 'blue light' services including Surrey Police, Surrey Fire and Rescue and South East Coast Ambulance service (SECAmb) and a Surrey and Borders Foundation Trust.

The suicide by female nurses brief report (The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH). Suicide by female nurses, 2020) found that:

- More than half of the nurses who died were not in contact with mental health services.

- Self-poisoning rates among female nurses were high.

- Female nurses have a suicide risk 23% higher than in women in other occupations.

The ABC framework of nurses' and midwives' core work needs:

- Autonomy - the need to have control over one's work life, and to be able to act consistently with one's values

- Authority, empowerment and influence

- Justice and fairness

- Work conditions and working schedules

- Belonging - the need to be connected to, cared for by, and caring of colleagues, and to feel valued, respected and supported

- Team working

- Culture and leadership

- Contribution - the need to experience effectiveness in work and deliver valued outcomes

- Workload

- Management and supervision

- Education, learning and development

Source: The courage of compassion Supporting nurses and midwives to deliver high-quality care, West et al 2020 (KF).

Nationally there has been a reported increase in deaths by suicide amongst health and social care staff. Key risk factors have included:

- Working long hours

- Increased work pressures

- Increased demand for services

- Reduction in the workforce.

Military veterans

The strategy consultation with health and social care professionals in Surrey reported high rates of post-traumatic stress, alcohol misuse, homelessness and poor mental health amongst military veterans.

Farmers and agriculture workers

National data shows that suicide rates in farmers are among the highest in any occupational group and the risk of suicide is also higher amongst those working in specific agricultural roles such as harvesting crops and rearing animals. This is also usually correlated to increased access to means. There is no data or information on the prevalence of mental health or suicide amongst farmers and agricultural workers in Surrey. However, the Farming Community highlights that nationally high levels of stress and depression exist in this group. (Farmers Community Network, Cited 1 February 2019). A key reason for this is isolation due to long working hours and work-related stress and pressures.

What the Surrey Suicide Prevention Partnership will do:

- 2.1 Reduce LGBTQI stigma through awareness, education and training. This will include raising awareness of appropriate language.

- 2.2 Ensure that the Autism workstream in Surrey includes suicide prevention.

- 2.3 Deliver a targeted and coordinated men's mental health project in Surrey.

- 2.4 Promote connectedness and building social capital together by decreasing isolation, encouraging adaptive coping behaviours, increasing belongingness and to help build resilience in the face of adversity. Engage with wider community initiatives to demonstrate the contribution to this agenda.

- 2.5 Engage with carers networks and promote support available. Monitor carer assessments and support available via primary care to ensure it is linking effectively.

- 2.6 Develop a Gypsy Roma Traveller suicide prevention work plan, co-designed with the GRT community that includes education and awareness, mental health support, crisis support and postvention support.

- 2.7 Embed suicide prevention in workplace health.

- 2.8 Raise awareness of the "Joiner Model" working with people who may have autism and those with diagnosed autism.

- 2.9 Surrey partnership to work with the prisons to audit the prison suicide prevention plans and offer support and guidance.

- 2.10 Develop a plan in Surrey to deliver mental health awareness and support to gamblers in Surrey.

- 2.11 Suicide prevention is to be embedded in domestic abuse services.

- 2.12 Domestic abuse awareness is embedded in all mental health services.

- 2.13 Conduct Equity Audits on access to mental health support to include ethnicity.

- 2.14 Workplace Health for Clinical and Blue Light Services needs to systematic consideration.

- 2:15 Target workplace mental health projects to key high-risk groups.

- 2.16 Map the mental health awareness and mental health support in Surrey for serving Armed Forces Personnel, Veterans and their families. Where gaps are identified work with existing partnerships to identify opportunities to respond to the gap.

Priority 3: reduce access to means by promoting suicide safer communities

The National Suicide Prevention Strategy Third Progress Report (Department of Health, 2017) highlights that in order to reduce access to means of suicide we should:

- Identify high risk locations.

- Put safeguards in place to prevent suicides.

- Be aware of emerging suicide methods.

- Work with local media around sensible reporting of suicide.

On average 65% of deaths occurred in the deceased's own home, with 35% in a more public place or someone else's home.

50% of deaths in young people ages 10- 14 year old was in a public location.

It is important that high risk locations are identified quickly through the suicide response work and response plans are developed in partnership with key agencies.

It is also important to reduce the access to means that have been identified in Surrey cases and nationally. This should include working with NHS England, Trading Standards, Local Retailers, clinical staff and key frontline staff to identify and reduce key means that may increase the risk of suicide.

What the Surrey Suicide Prevention Partnership will do:

- 3.1 Use the real-time suicide surveillance data to inform suicide response work.

- 3.2 Develop a local suicide high risk location working group.

- 3.2 Continue to raise awareness of responsible reporting of suicide in the media.

Priority 4: reduce attempted suicide amongst children and young

Young people face many pressures in life. Education, family, friendships, hormonal changes and virtual environments can increase negative emotions and behaviours. Additionally emerging evidence also confirms that 1.5 million children and young people in England will need support for their mental health as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic over the next three to five years.

Self-harm

Self-harm is a useful indicator to view alongside suicide data.

Instances of self-harm are more common in children and young people, and as many as 25.7% of women in England between the ages of 16 to 24 report that they have self-harmed at some point in their lives. As self-harm remains the greatest predictor of suicide, a prevention plan which acknowledges this concern is paramount to reducing the overall rates of suicide among the nation's youth.

Factors present in suicide reviewed by Child Death Overview Panels in England

Based on child death reviews (England) 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020

- Household functioning

- Loss of key relationships

- Mental health needs of the child

- Risk-taking behaviour

- Conflict within key relationships

- Problems with service provision

- Abuse and neglect

- Problems at school

- Bullying

- Medical condition in the child

- Drug or alcohol misuse by the child

- Social media and internet use

- Neurodevelopmental conditions

- Sexual orientation / identity and gender identity

- Problems with the law

Between 1 April 2019 and 31 March 2020 these factors were present in the suicide reviewed by the Child Death Overview Process in England (NCMD, 2021):

Feedback from professionals working with children and young people in Surrey:

- Young people are concerned about the loss of opportunities

- Lots of young people missed out of socialisation

- An increase in poor mental health in children and young people

Healthy Schools Approach: positive outcomes for children and young people

Surrey Healthy Schools is a whole system, evidence-based approach that uses proportionate universalism (improvements should be allocated proportionally to population need.). It builds upon strengths to reduce vulnerabilities, applying prevention, intervention and targeted support to reduce inequalities, promoting positive outcomes for children and young people.

Surrey Healthy Schools aids communication, cohesion and partnership working across the system and is aligned through Surrey's strategies and their recommendations, commissioning, ethos and culture.

It is a multifaceted approach that acts to unify the work of services, partners, the third sector and schools.

There are 5 key themes to Surrey Healthy Schools – one of which is Personal, Social, Health, Economics (PSHE) Education. PSHE is the curriculum subject into which the statutory relationships education, relationships and sex education, and health education are subsumed.

All Surrey schools can access the Surrey Healthy Schools Self Evaluation Tool which progressively supports PSHE leaders in schools through a series of key pedagogical standards with signposting – to assist subject development enabling the school to better meet the needs of pupils.

From September 2022 all schools can access the PSHE Essentials free training offer to support effective PSHE curriculum development.

PSHE Essentials free offer for all Surrey schools

- Surrey Healthy Schools Approach training

- Whole School Approach to building a thriving school culture

- PSHE: developing resilience

- PSHE Essentials: growing healthy relationships (primary)

- PSHE Essentials: growing positive physical and mental health and wellbeing (primary)

- PSHE Essentials: advancing healthy relationships (secondary)

- PSHE Essentials: progressing positive physical and mental health and wellbeing (secondary)

School transition

Children and young people may have to move schools due to a house move, parental separation, bereavement, parental job change or due to difficulties in their existing schools. Moving schools increases the risk of social isolation and lack of connectedness. These have all been identified as risk factors for poor mental health. Support is needed for young people when they move schools.

As part of age transition children and young people will transfer from school to their chosen route of further education/ higher education or employment.

The transition increases the risk of poor mental health due to loss of social structure, change of schedule and, in some cases, a fear for the future.

Frontline professionals report young people aged 16- 25 experiencing high levels of poor mental health due to lack of hope, concerns over money and financial security, debt and relationship breakdowns.

Thrive framework

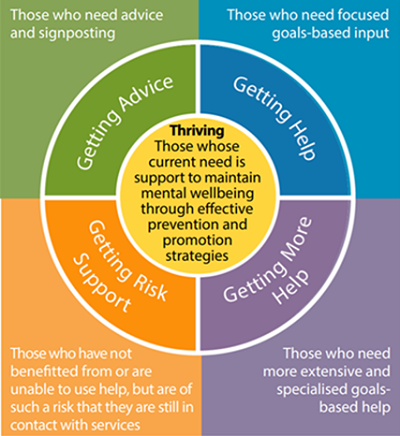

The THRIVE Framework places an emphasis on the prevention and promotion of mental health and wellbeing for everyone. All children, young people and their families are empowered by having an active involvement in the decisions made about their care, which is an essential part of the approach. There are five different needs based groups within the framework:

Thriving: those whose current need is support to maintain mental wellbeing through effective prevention and promotion strategies.

- Getting advice - those who need advice and signposting

- Getting help - those who need focused goals-based input

- Getting risk support - those who have not benefitted from or are unable to use help, but are of such a risk that they are still in contact with services

- Getting more help - those who need more extensive and specialised goals-based help.

For this important priority, the following arrangement will be set up in Surrey. The governance will report into the Health and Wellbeing Board plus key boards as appropriate to the learnings/ emerging issues. The expectation of all who participate in the delivery structure are:

- Drive suicide prevention in their organisation

- Deliver key actions within the plan.

- Share emerging gaps and issues with the group.

- Challenge the system where there is a risk.

- Support colleagues within this partnership by ensuring that there is support, openness, respect, confidentiality and no shame or blame.

Surrey's children and young people suicide prevention partnership structure

Oversight group - meet every 6 weeks

- An overall children and young people suicide prevention oversight group with 5 - 8 members. This group will report into the Surrey suicide prevention strategy group.

- As part of the oversight group an extraordinary meeting for networking group: meet quarterly input/ show and tell

| Group 1 Prevention and early intervention | Group 2 Mental health services and commissioning | Group 3 Learning and postvention |

|---|---|---|

| Education and awareness | Commissioning | Postvention support |

| Building resilience | Service provision | Suicide response |

| Early intervention | Service delivery | Learning from serious incidents related to attempted suicide or self-harm |

| Families support | Service needs, gaps | Postvention support |

| Service development | ||

| Recovery |

What the Surrey Suicide Prevention Partnership will do

- 4.1 Deliver the new children and young people suicide prevention structure.

- 4.2 Embed Healthy Schools approach across all Surrey Schools.

- 4.3 Ensure that children and young people receive mental health support in a timely manner.

- 4.4 Roll out a suicide prevention toolkit across all educational establishments (e.g. schools, colleges and universities).

- 4.5 All professionals working with children and young people receive mental health and suicide prevention awareness training.

- 4.6 Ensure we have the evidence and intelligence to inform children and young people suicide prevention across the spectrum.

- 4.7 Ensure that young people and their families are at the heart of the work and co-production is embedded across the mental health pathway.

- 4.8 Ensure we follow best practice guidance where there are national set standards and adopt good practice/ learning from other areas.

- 4.9 Ensure that there is strong leadership, governance and support to delivery of suicide prevention in Surrey.

- 4.10 Review the whole children and young people mental health offer in education on an annual basis.

- 4.11 Ensure that self-harm prevention and intervention is embedded across the existing children and young people workstreams.

- 4.12 Enhance support and guidance to educational establishments regarding screening for suicide risk and the services which schools and other settings can refer to (i.e. services as appropriate and Mindworks).

- 4.13 Explore Mental Health Support Teams' role for independent sector, home schooling, alternative provision.

- 4.14 Develop postvention support for children and young people in line with national recommendations and guidance.

- 4.15 Identify the key concerns of young people ages 16 - 25 and develop local plans to respond to this.

Priority 5: provide better information and support to those bereaved by suicide

The provision of support after a suspected suicide is critical to addressing suicide risk and improving the mental wellbeing of people who have been bereaved by suicide.

Suicide bereavement leaves people at a higher risk of suicide themselves. A survey in 2010 found that friends and relatives of people who die by suicide have a 1 in 10 risk of making a suicide attempt after their loss. On average 92 people a year die by suicide in Surrey.

Estimates vary on how many people are affected by each suicide – ranging from six to 60 people. In Surrey around 920 people could benefit from support in one year, although it is unlikely that all people bereaved by suicide would come forward for support. Some may feel that they do not need support, others may feel concerned about the stigma of suicide.

Compared with people who have been bereaved through other causes, individuals who are coping with a loss from suicide are more likely to experience increased risk of psychiatric admission, depression, and grief beyond 6-12 months of bereavement which severely disrupts the person's ability to carry out normal activities such as work, relationships, and social functioning.

National survey data suggests that two thirds of people in the UK bereaved by suicide receive no formal support from health or mental health services, the voluntary sector, employers nor education providers.

The cost of a suicide has been calculated as £1.67 million, with 70% of that figure representing the emotional impact on relatives. An economic evaluation of an outreach service in Australia demonstrated a direct cost saving of around AUS$800 (around £433) each year for every person supported.

People bereaved by suicide are 80% more likely to drop out of education or work than their peers, while 8% of young adults bereaved by suicide surveyed had dropped out of an educational course or a job since the death.

The national and local policy and strategy context stresses the importance of suicide bereavement support. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health set out an ambition to reduce the number of suicides in England by 10 per cent by 2020 from a 2016 baseline. Providing support for people bereaved by suicide is a key objective of the national suicide prevention strategy for England. Supporting people bereaved by suicide was highlighted in the Health Select Committee's 2017 inquiry into suicide prevention, and the Government's response to the Inquiry.

Death by suicide can affect a broad range of people. The impact of the death can be affected by the relationship of the individual to the deceased, whether the person witnessed/ found the deceased, and the emotional struggles and resilience skills of the individual.

The people affected can be considered in four groups:

- Group 1: Suicide bereaved long-term: Family, partners, close friends.

- Group 2: Suicide bereaved short-term: Friends, peers, close work colleagues, longstanding health/ social care workers, teachers.

- Group 3: Suicide affected: First responders (family, friends, members of the public, police, paramedics), those directly involved such as train drivers, neighbours and local residents, teachers, classmates, co-workers, health/ social care staff.

- Group 4: Suicide exposed: Local groups, communities, passers-by, social groups, faith groups, acquaintances, wider peer groups including those via social media contacts (for example Facebook friends).

A key action in the NHS Long term plan is to roll out suicide bereavement support services across all Integrated care systems (ICSs) by 2023/24 (NHS, 2019).

National recommendations suicide bereavement (McDonnell S, November 2020):

- The implementation of national minimum standards in postvention services

- A national online resource for those bereaved or affected by suicide

- Campaign to raise awareness of the impact of suicide bereavement

- Suicide bereavement training for front line staff. Evidence-based suicide bereavement training should be mandatory for those who provide postvention services.

- Support for people with risk taking behaviours

- Workplace suicide bereavement support

- Further research on the impact of suicide.

Suicide bereavement in Surrey

- In Surrey 22% of adults who died by suicide had dependent children and 38% had adult children.

- At least 92 children under the age of 18 and at least 171 adult children have lost a Surrey parent to suicide over the four-year period (Surrey suicide audit 2017- 2021).

Surrey has a suicide bereavement support service. The service is contracted to provide a welfare assessment, advocacy and support to people bereaved by suicide. Due to funding constraints the service is not commissioned to provide suicide bereavement counselling.

The existing contract is focused on suicide bereavement support for adults. There is a gap in provision for children and young people.

Priority 5: what the Surrey Suicide Prevention Partnership will do

- 5.1 Explore suicide bereavement counselling provision in Surrey.

- 5.2 Provide a suicide bereavement support service for children and young people.

- 5.3 Raise awareness of suicide bereavement.

- 5.4 Train frontline professionals and community members of suicide bereavement awareness.

- 5.5 Continue to fund suicide bereavement support in Surrey.

Priority 6: prevention of suicide among identified high risk groups particular those with known mental ill health

Chronic pain

A review on the suicide risk associated with chronic pain found that suicide risk is significantly higher in people living with chronic pain, but this risk as attributed to the psychosocial rather than the physical aspect of pain.

In the Surrey suicide audit, pain was identified as a key contributing risk factor. There is need for more work around pain and mental health.

Substance use

The use of alcohol or substances increases the risk of poor mental health, increased risk taking behaviours and increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

In Surrey 57% of deaths by suicide acknowledged either alcohol or substance use before death. This largely covers individuals who had a combination of long established alcohol use and/ or drug misuse. However, only 3% of the individuals who died by suicide were in contact with specialist substance misuse service prior to death,

There is also a close link between drug related deaths and suicides. There have been some cases of drug related death that could have been suicide; and some suspected suicides that were later deemed as drug related deaths. The drug related death work and the suicide prevention work should align to share learning and opportunities for joined up intervention.

Mental health

National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health, Social and clinical characteristics of mental health patients dying by suicide in the UK (NCISH, 2022)

Socio-demographic characteristics of patients who died by suicide in the UK (2009 - 2019):

- 66% male

- 13% aged 65 and over

- 48% living alone

- 73% unmarried

- 47% unemployed

- 7% ethnic minority group

Clinical and behavioural characteristics of patients who died by suicide in the UK (2009 - 2019):

- 53% comorbid diagnosis

- 21% ill <12 months

- 14% last admission was a readmission

- 64% self-harm

- 47% alcohol misuse

- 37% drug misuse

The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health, Social and clinical characteristics of mental health patients dying by suicide in the UK report shows the main social features of patients dying by suicide in the UK. The report highlights that these 66% of patients identified as male patients. There were high rates of social adversity and isolation. 53% of patients had a comorbid diagnosis. 64% of patients had a history of self-harm. 47% of patients had a history of alcohol use and 27% had drug use.

Medication prescribing

People are often prescribed medication to manage suicidal thoughts. Whilst treatment is important this needs to be combined with regular follow ups as research show that suicide rate increases in the first 28 days after starting and stopping antidepressant treatment (Coupland, 2015).

In Surrey, an evidence-based criteria should be developed to identify people who need to be followed up when they have been prescribed medication. The follow up is recommended for day 3, day 7 and then in line with the needs of that person.

A safety plan should be developed with people prescribed medications which how they will manage in the time it takes for the medication to have an impact.

Recommended questions for medication follow up:

- Have you collected medication?

- Have you started medication?

- When are they taking it?

- How are they feeling?

- Check the safety plan

In Surrey over one third of individuals who died by suicide had a previous history of self-harm. In most cases, people who self harm do not present for medical attention. Evidence shows that self-harm is higher in females than males.

Crisis care

The Mental Health Crisis Care Concordat is a national agreement between services and agencies involved in the care and support of people in crisis. It sets out how organisations will work together better to make sure that people get the help they need when they are having a mental health crisis.

The Concordat focuses on four main areas:

- Access to support before crisis point – making sure people with mental health problems can get help 24 hours a day and that when they ask for help, they are taken seriously.

- Urgent and emergency access to crisis care – making sure that a mental health crisis is treated with the same urgency as a physical health emergency.

- Quality of treatment and care when in crisis – making sure that people are treated with dignity and respect, in a therapeutic environment.

- Recovery and staying well – preventing future crises by making sure people are referred to appropriate services.

In Surrey there is already a number of mental health crisis services that can be accessed by people having thoughts of suicide.

Safe Havens

There are four Safe Havens in Surrey. They provide out of hours help and support to people and their carers who are experiencing a mental health crisis or emotional distress. They are designed to provide adults with a safe alternative to A&E when in crisis.

The Safe Havens are open evenings, weekends and bank holidays.

The Safe Havens are provided in partnership between Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (SABP) and third sector mental health specialists. Peer support from people with lived experience of mental health issues is also increasingly available.

The current Safe Haven provision in Surrey is not accessible to everyone. Whilst they are near public transport, they are not easy to access from people living outside the area. This is due to the public transport networks and the cost of transport to get there and back. These concerns have been reported from people living and working in Spelthorne, Tandridge and Waverley.

Crisis overnight support service

National evidence shows that a short break away from home can support recovery from a mental health crisis and prevent a lengthier mental health hospital admission.

Improving safety in mental health care

National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, 10 components of safety in mental health care (NCISH, 2022)

10 ways to improve safety:

- Safer wards

- Early follow-up on discharge

- No out-of-area admissions

- 24-hour crisis teams

- Family involvement in 'learning lessons'

- Guidance on depression

- Personalised risk management

- Outreach teams

- Low staff turnover

- Services for dual diagnosis

SABP already audit themselves against foundations standards that covers these 10 components.

It is recommended that the Surrey suicide prevention partnership works with private providers to ensure that they are regularly independently audited against these ten components. Delegated Commissioners could develop a governance process to ensure that services that are meeting these ten components.

Preventing suicide (Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust)

Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (SABP) is the leading provider of health and social care services for people of all ages with mental ill-health and learning disabilities in Surrey and North East Hampshire.

They deliver care across 140 services, all of which are registered with the Care Quality Commission. Individual treatment and support, which help people work towards recovery, is at the heart of everything that they do.

Their services are provided in community settings, hospitals and residential homes with an emphasis on providing local treatment and support close to people's homes wherever possible.

Preventing suicide is a key objective for SABP. The trust will focus of four key areas:

Education and funding

- They will establish an annual coordinated training plan for mental health awareness and suicide prevention targeted to high-risk groups.